Download PDF of this article here

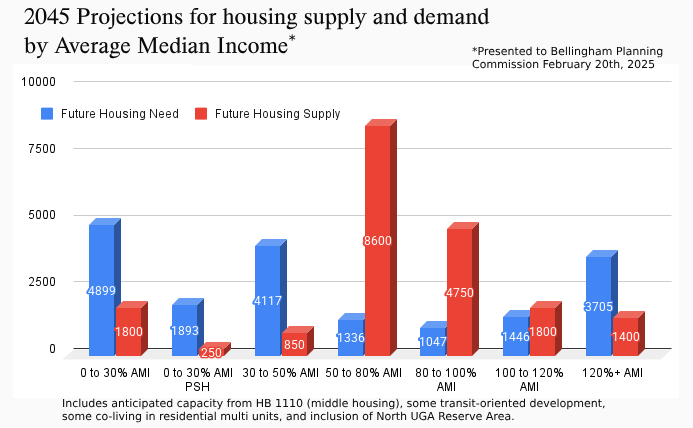

Bellingham’s Future Workforce Housing (30-50% AMI) Projections –

- Estimated Housing Capacity (supply) is 850, and

- HAPT Housing Allocation (need) is 4117, and

- There is an excess capacity for higher end housing due to recent city and state zoning changes and policies benefiting those with higher incomes.

When the Estimated Housing Capacity is significantly lower than the HAPT (Washington’s Housing allocation Planning Tool) Housing Allocation, as with the 30-50% AMI graph above, it signals a major mismatch between the potential for housing development under current regulations and the projected housing need.

The Right Changes to Local Policies and Zoning are Needed

A situation where capacity (supply of 850) is far less than the allocation (demand of 4117) signals a significant under-capacity in the jurisdiction’s current land use and zoning framework to meet projected housing needs for Bellingham’s Workforce. Inclusionary Zoning (IZ) and similar regulatory tools become not just helpful, but arguably essential, for creating the affordable housing supply needed. This is because the private market, driven by profit, does not produce housing affordable to households earning 30-50% AMI without subsidies or regulatory requirements. Construction costs, land prices, and financing models often make it economically unviable for developers to build and operate housing at these rent levels if relying solely on market rents.

Changes in Zoning for Market Rate Supply Often Makes the Problem Worse

As the graph portrays increased supply alone doesn’t create affordability for those earning 30-50% AMI, our workforce. While increasing overall housing supply can help moderate housing costs at the median level over time, it’s less effective at directly creating housing affordable to the lowest income brackets. Market-rate units, even in a larger supply, will still be priced at market rates, which are often far beyond the reach of 30-50% AMI households. “Filtering”, or trickle down economics, (the idea that new market-rate housing eventually makes older housing more affordable) is a slow and imperfect process and often doesn’t reach deeply affordable levels.

Housing for households at 30-50% AMI requires a deliberate and targeted approach to affordability. Inclusionary Zoning, alongside other tools, can provide this targeted affordability by directly requiring AND incentivizing the creation of affordable units within new developments.

Increased development spurred by up-zoning, such as the reduction of Parking Minimums, will produce market-rate housing. This will potentially lead to displacement of lower-income residents as land values and rents rise due to increased property values and gentrification. IZ can help ensure that an important portion of new development is affordable and benefits existing residents, including those at lower AMIs.

How Inclusionary Zoning Works:

- Mandatory AND Incentive-Based IZ:

- Mandatory IZ: This requires developers of market-rate projects to include a certain percentage of units that are affordable to specified income levels (e.g., 30-50% AMI or up to 80% AMI, often with tiered requirements). This is more effective at guaranteeing affordability but can be more politically challenging to implement and might face developer pushback unless incentives are offered.

- Incentive-Based IZ: This offers incentives (like density bonuses, expedited permitting, fee waivers, parking requirement reductions) to developers.

- Affordability Levels and Terms: Crucially, for targeting 30-50% AMI, the IZ policy must be designed to:

- Require, with incentives, units at deeply affordable levels: The AMI targets in the IZ policy must specifically address the 30-50% AMI range. Simply targeting 80% AMI units may not adequately serve this very low-income population.

- Ensure long-term affordability: Affordability restrictions (e.g., through deed restrictions, covenants) must be in place for a significant period (e.g., 30-50+ years, or ideally in perpetuity) to ensure that the units remain affordable over time and don’t revert to market rates.

- Depth of Affordability and Subsidy Stacking: To make units affordable at 30-50% AMI, even with IZ, it may be necessary to “stack” other subsidies and resources on top of the IZ requirements. This might include:

- Public funding sources: Local, state, or federal affordable housing funds (e.g., Community Development Block Grants, HOME funds, Low-Income Housing Tax Credits if applicable to IZ units).

- Land value subsidies: Using publicly owned land at below-market cost for affordable components of IZ projects.

- Rent subsidies/housing vouchers: Project-based vouchers tied to IZ units can help bridge the gap between deeply affordable rents and operating costs for landlords.

Beyond Inclusionary Zoning:

While IZ is vital in this scenario, it’s rarely used alone. A comprehensive strategy to address housing needs for 30-50% AMI households likely requires a multi-faceted approach, including:

- Direct Public Investment in Affordable Housing: Significant public funding for the development and operation of deeply affordable housing (public housing, non-profit housing).

- Rent Subsidies and Housing Vouchers: Expanding access to tenant-based and project-based rental assistance programs.

- Preservation of Existing Affordable Housing: Protecting existing subsidized and naturally occurring affordable housing from loss or conversion to market rates.

- Supportive Housing: Integrating housing with supportive services for extremely low-income individuals and families, including those experiencing homelessness.

- Land Use and Zoning Reform Beyond IZ: While IZ focuses on affordability within new development, broader zoning reforms to increase overall housing capacity (as discussed previously) are still important to address the overall supply shortage and moderate market-wide housing cost pressures.

In conclusion, if HAPT numbers point to an extreme need for housing primarily for households earning 30-50% AMI, Inclusionary Zoning becomes a critical regulatory tool to ensure that a portion of new housing supply is genuinely affordable to this demographic. However, IZ needs to be carefully designed with appropriate affordability targets, long-term restrictions, and potentially coupled with other subsidies and supportive policies to be effective. It’s also important to recognize that IZ is often part of a broader, more comprehensive affordable housing strategy that includes direct public investment and other complementary approaches, intensifying the need to begin as soon as possible.